The Symposium

3 of Plato's early and middle dialogues are rooted in the praise of same-sex relationships: Lysis (which is about friendship), Phaedrus (which is about romantic love and rhetoric), and Symposium (which we read). Despite these writings, teh world that Plato lived in had a profound im[pact on him, and he ended his life "a bitter fascist and completely departed from his happier, humanly honest early work". Idealism turned to bitterness, and Plato, in his work "Laws", suggests that "all but marital poetry is banished and sexual activity between men is forbidden". However, this is a far cry from his earlier works.

"Symposium" is a dinner party where men met to eat, drink, and talk. This stems from the Greek tradtition of BANQUET LITERATURE. This specific dinner party took place in 416 B.C. in the home of Agathon, a then "up and coming" 31-year old "tragic poet". A few days before the banquet, he had won the poetry laurel in a festival at the Theater of Dionysus in Athens in front of 30,000 people. The other attendants were: Socrates (then 53), he came with Aristodemus. Phaedrus, Pausanias (a disciple of a Sophist Philosopher), Eryximachos (a physician), and Aristophanes (32 year old comic playwright). Teh last to join is Alcibiades, the 35 year old whom Socrates had a crush on. The dialogue is recounted by Apollodoros, who had been told by Aristodemus-- but 15 years had passed since the actual party. The topic of discussion that night: LOVE.

The discussion begins with a passing comment by Eryx based on something Phaedrus has said: that "love has yet to receive the praise it is due"-- so they decide to change that. What ensues is an honest and human praise and explanation of LOVE.

Short Summaries of Speeches:

Phaedrus says that LOVE is ther oldest of the gods and of the greatest good for man. "For I cannot say what is greater good for a man in his youth than a lover, and for a lover, his beloved". Love leads one toward what is good, what is beautiful and virtuous, and is then necessarily beneficial.

Pausanias takes Phaedrus' idea and divides it in 2: Common Love and Heavenly Love. Of Common Love, he says, "This si the love which inferior men feel. Such persons love women as well as boys; next when they love, they love bodies rather than souls". This love is deficient in virtue because what is important is not who they love but that they love. The explanation of Heavenly Love is perplexing, but he does say that it is the "elder of the two loves" that is without violence, more knowledgeable, and more peacable, and "consequently those inspired by this love turn to the male because they feel affection for what is stronger and has more mind". However, he seems to ignore the violence inherent in war practices, esp. in the discussion about Achilles and Patroclous, who as you can see are considered without a doubt lovers-- not merely friends. His speech has some interesting spots, including a discussion of how love can be useful in politics and with such statements as, "it is called better to love openly than secretly".

Aristophanes has hiccups and passes to Eryximachos, who expands on the "dual love" concept. He speaks in physician terms, saying, "there is one love for the healthy and one for the diseased, but both kinds of love are necessary, and what is sought is a good balance. Eryx's speech is dull.

"Lovers don't finally meet somewhere. They're in each other all along." --Rumi

This quote by Rumi demonstrates the thinking of Aristophanes.

Aristophanes' speech is the stunning centerpiece of "The Symposium". He uses literary skill to spin for the men an unsurpassed fable of imagination. He posits that we bagan as "3 sexes", not 2: male (sun), female (earth), and hermaphrodite (moon). Man was first a round creature whose spine and ribs framed a circular body from which extended 4 arms, 4 legs, 1 head with 2 faces looking front and back, 4 ears, and 2 sets of genitals. Man was strong and full of ambition, so he attacked the gods. The gods decided not to wipe him off the face of the earth, and Zeus, king of the Gods, came up with a solution: he would weaken man by cutting him in half. This would increase man's numbers and double the worshippers of the gods. Zeus adds that if this doesn't work, then he'll slice them up into quarters, so they might "hop about on one leg". Man's face was turned toward the cut to remind him fo the punishment, and the naval was left as a permanent reminder. So then comes the explanation of LOVE:

"So when the original body was cut through, each half wanted the other, and hugged it. They threw their arms around each other desiring to grow together in teh embrace, and died fo starvation and general idleness because they would not do anything apart from each other".

Zeus took pity and moved their genitals to the front so that they might make love with each other adn bring forth children; their love was then sufficiently self-contained in a round 8-limbed physical whole (2 hearts, 1 soul). SOULMATES. The union of the male with female is for procreative purposes; the union of male with male leads to satisfaction and rest and allows each man afterward to "turn toward the business of life". Hermaphrodites became men who are fond of women (adulterers are from this sex); women who came from only females became lesbians, and men who were of the all-male sex now pursue the love of other men-- even as boys [these are the bravest and best of all men]. When they find their other half, they recognize it and are lovers for life... we are all incomplete-- UNTIL.

Agathon discusses love's embodiment of justice, temperance, courage, and wisdom, but it pales in comparison to what comes before.

Ditoma's speech is a syntehesis of the others. Alciabades, Socrates' lover, stumbles in durnk and is angered to find Socrates sitting next to the handsome Agathon. He sits beside his lover with a half gallon of wine (yeah, they knew how to party!). Alciabades' speech (in praise of Socrates) displays Socrates as a lover and compares the others' words with deeds; his evidence is his own affair with Socrates. He describes meeting Socrates, then in his mid-30's, Alciabades a teen. Socrates stays overnight in his bed, but they do not have sex. They eventually share a kind of "chaste-lover's intimacy"-- theirs is a spiritual love, a love of the mind and heart rather than the "groin". This is what we come to know as PLATONIC love.

Plato's Symposium provides a forum for prevalent Victorian, Edwardian and even later attitudes, particularly in England and America, toward Greek Homosexuality. It illustrates a "clash of cultures". The value that Plato attributes to such loves as motives to virtue and philosophy are at odds with modern Christian notions (or interpretations thereof). Christendom has not encouraged passionate same-sex friendships and view them, if taken any further, as having "degenerated into fearful evil". Love between males is (today) dismissed as shameful, immoral, and indecent. But how to we reconcile so noble a philospher who espouses such a "seemingly degrading" view?

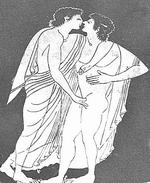

Much of the homoerotic discourse in The Symposium draws from legend and mythology. Homoerotic literature "grew from the themes of male beauty and the delights of young men and boys". We've already discussed the social pattern: a younger man or teen called EROMENOS (beloved) was sought out by an older male called ERASTES (lover)-- who might already be married. Because wives and daughters were basically secluded from outside life, boys and young men were naturally drawn to each other. Teh adult man was the aggressive pursuer and could openly court a younger male; the boy played the female role and was never seen as the aggressor; the relationship was only "solidified" after a period of courtship.

Strict rules bound both parties. While the eromenos-erastes relationship was sexual, it was mainly educative. The older male made the younger "pregnant with" a respect for the masculine virtures of courage and honor. Candor int he expression of love and sexuality would not have shocked Plato's audience as it does today in our "so-called liberated society". Outspokenness in such matters was far more natural to a culture that regularly practiced public fertility festivals, often featuring models of the male and female genitalia. [Of course in our time, we have a former Attny General-- John Ashcroft-- who thought it his business to cover up all of the "privates" of the nude statues around the White House, including the "spirit of justice".

The conclusion to our journey through Greek Literature: Socrates was the best erastes of all, the loving adult male teacher who sought to lead his eromenoi (male beloveds) on teh road to virtue...

The above is from the books: Lysis, Phaedrus, & Symposium: Plato on Homosexuality by Eugene O'Connor. And... The Gay Canon by Robert Drake.

The FIRST 3 SPEECHES:

Phaedrus: Love is the means of producing an honorable society. Love enables humans to "acquire courage and happiness".

Pausanias: 2 kinds of love-- stemming from 2 kinds of Aphrodite: Heavenly and Common. Common Love is inferior-- it is attraction to bodies rather than minds (intellect). There should be laws governing love affairs to eliminate the possibility of young men and women being taken advantage of before they are intellectually mature. Good and Bad lovers: Bad lovers feelings fade when teh body ages; good lovers love a goodness of character, and that kind of love is constant. The practice of "chasing our lovers' is a test. He speaks about slavery and that it is only right if the enslaved is gaining honor, virtue, wisdom and education in the relationship. Love is most heavenly when it is tested, and when the goal of the relationship is to gain virtue.

Eryximachus: Agrees with Pausanias that there are 2 kinds of love... but he adds, as a doctor, that he has learned that love is not limited to humans only, but to animals and plants as well.

Questions:

1. Having read Symposium, which of the offered speeches strikes at your heart most strongly, and describes the understanding of love you, presently, want to hold? If you could, would you extend that perception universally? Why or why not, and what would be the results?

2. What is to be made of Platonic Love? Is love without sex satisfactory?

3. Is there virtue-- beauty-- in casual sex, and if so, what is it?

4. What is the fundamental wrong with pedophilia? What is it that makes sex "unhealthy" vs. "healthy"?

HEDWIG AND THE ANGRY INCH

James Cameron Mitchell's source of inspiration for this musical was Plato's Symposium. Clearly there are different types of love, and "Symposium" explores EROS specifically-- not love of god or family-- this is romantic love. Platonic love could be romantic... it could be sexual, but it stops short.

1. Discuss the idea of becoming 'whole' or 'complete'. What completes 1 person may not be satisfactory to another. Both texts discuss the idea of "soulmates" or of finding our "other halves". What is Hedwig's quest, and what does she learn?

2. Discuss the idea of people writing on your soul. How many times can you be in love? Can we have only 1 soulmate? Does that person have to be a lover?

3. Discuss sexuality as being "black and white"-- or gray. Why do we try so hard to catagorize sexuality in our modern society? What effect does this have on society?

4. There's a discussion in the book about what is beautiful and what is ugly. Apply this to the film.

5. Consider this: Plato often discusses the father-son relationship and the "question" of whether a father's interest in his sons has much to do with how well his sons turn out. A boy in ancient Athens was socially located by his family identity, and Plato often refers to his characters in terms of their paternal and fraternal relationships. Socrates was not a family man, and saw himself as the son of his mother, who was apparently a midwife. A divine fatalist, Socrates mocks men who spent exorbitant fees on tutors and trainers for their sons, and repeatedly ventures the idea that good character is a gift from the gods. Crito reminds Socrates that orphans are at the mercy of chance, but Socrates is unconcerned. In the Theaetetus, he is found recruiting as a disciple a young man whose inheritance has been squandered. Socrates twice compares the relationship of the older man and his boy lover to the father-son relationship (Lysis 213a, Republic 3.403b), and in the Phaedo, Socrates' disciples, towards whom he displays more concern than his biological sons, say they will feel "fatherless" when he is gone. Many dialogues, like these, suggest that man-boy love (which is "spiritual") is a wise man's substitute for father-son biology (which is "bodily"). Now think of Tommy-- and apply this theme. Think of how Tommy's relationship with his father impacts his view of "God the Father" and his relationship with Hedwig.

6. There's a discussion about "birth" in the book... manifested as a discussion about "creation" in the film. If all human beings desire "procreation", then how do relationships other than male/female-- or relationships with no possibility of producing a child-- satisfactory? What is Hedwig's "baby"?

7. Discuss Hedwig/Tommy's relationship in terms of Erastes-Eromenos. Is this form of pederastry okay? Why? Where do we draw the lines with this type of relationship?

Instructor's Thoughts:

"Dans ma vie, je t'aimerai plus". -The Beatles

"In my life, I will love you more".

These words appear on the wedding bands that my husband and I wear... I designed them a couple of years into our marriage after never feeling satisfied with the traditonal vows that we made during our traditional marriage ceremony.

Everyone has a different view of "soulmates". I believe that there are people who come into our lives and "write on our souls"-- they shape who we are. Sometimes this can be a boyfriend/girlfriend, a lover, a platonic friend, or a mentor. There have been many people who have written on my soul.

What my husband and I vow to each other is that in our lives, we will love each other MORE... not only. Can a person be "in love" multiple times throughout their lives? I think so, although others may disagree. Staying in love is hard work... you have to decide to put someone else first. You have to make the decision to care over and over again. You have to not only accept love, but give it as well. And when one person in a relationship faulters, the other must work even harder to to guide the relationship back on track. People give up on relationships too easily sometimes; people also tend to hide their true feelings at times to avoid jealousy. Once you fall in love with a person, it is okay to continue loving them, whether or not the relationship works out.

I believe that love is created, and like every other creation, its essence lives on-- even in "death". Jealousy is a weakness that we must overcome...

While love does not need to be confined to one person, faithfulness does. While faithfulness is a modern convention (as you know, the Greeks, and many other cultures of people, did not consider faithfulness a virtue). However, it is part of the human condition for us to want to be loved "above all else"-- to be that one special person in someone else's life. This does not mean that we need to disregard our former relationships, just redefine them. We deserve fulfillment-- but we must work at it... we are all human, and human beings, by nature, are imperfect beings. In fact, perfection is non-existent, which is why many of us are so disappointed in relationships at times: we have too many expectations!

It is my hope that all of you find your "other half"... find fulfillment and love in this world. What exactly this is may be different for each person. Cherish each person who brings love into your life... and pay tribute to the people who come into your life and "write on your soul!"

On Fate...

I often struggle with the concept of "fate". Does everything in life happen "for a reason"-- or is it all chance? Well, I just don't know. There are some things that happen that I can see "no good reason" for; one example would be the tragedy of 9/11.

I think that it is easier for us to believe in fate when we play a "survivor" role, rather than a "victim" role. For example, I go between being thankful for having an alcoholic father (because I know that the creative, thoughtful, introspective side of me comes from those experiences) to being angry (because I imagine having a normal childhood, free of anxiety and turmoil... and sometimes, that seems really nice!).

This applies to "love" as well. Sometimes we dismiss certain relationships that we go through as being "insignificant"... we sometimes use the word "regret". However, it is hard to imagine ourselves being who we are without having experienced everything that we have. I guess how you look at it depends on how comfortable you are with "who you are".

These entries are just random thoughts inspired by the texts and by our in-class discussions. I hope that the literature makes you "think" as well... no matter the outcome of your thoughts!

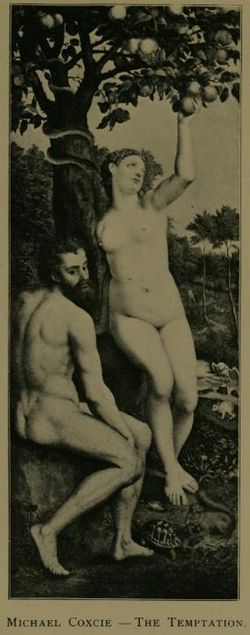

Creation Stories

Aristophanes story is a creation myth. There have been many creation myths throughout history; indeed, just about every culture ever present on Earth has had its own creation myth. Of course, the myth most familiar to us now is Genesis. It is the story of Adam in the garden of Eden. There are 2 distinct accounts of the story. The one more familiar to us, from the Torah, God breaths life into Adam-- thus creating the first man. Because Adam is lonely, God creates a partner for him by taking part of his rib and creating Eve. However, an earlier account of the story says that God (male and female) create the Male and Female simultaneously. Medieval Rabbis interpret this "first woman" and Eve as seperate beings. The first woman is called Lilith. The myth alludes to Lilith as a hypersexual female who is unwilling to be subdued by Adam and thus becomes either a demon or mother of demons in myths. Adam (or Brian) and Eve are parents to Cain and Abel. Adam lives for 930 years, according to the myth. But he and Eve are banned from the garden because they "eat the fruit from the forbidden Tree of Knowledge". From this myth, a cornerstone of Christianity was born-- that human beings are born sinners-- "original sin"-- and that sin must be washed away through baptism (what my kids call "magic water sprinkling" :) The serpent who tempts Eve is sometimes viewed as Satan. Modern-day Christians take the myth literally; some suggest that the serpent successfully tempts Eve, who successfully tempts Adam-- and therefore, more blame is placed on the woman as the "first sinner". However, I have never personally been able to reconcile this, as the Church also teachers that the male is the "head"; he must follow in Christ and guide his female partner. He was created to be stronger than his female counterpart. She alone did not lose paradise-- paradise was lost because of a joint "sin"; if either should carry more blame, then shouldn't it be Adam, since Eve was his subordinate? I personally find it interesting that Mitchell combines both Aristophanes' myth and Genesis to explore his own questions about how and why we are made the way we are-- to explore the "essence of being".

Common Elements in Creation Myths

Lindsey Murtagh It is in the nature of humans to wonder about the unknown and search for answers. At the foundation of nearly every culture is a creation myth that explains how the wonders of the earth came to be. These myths have an immense influence on people's frame of reference. They influence the way people think about the world and their place in relation to their surroundings. Despite being separated by numerous geographical barriers many cultures have developed creation myths with the same basic elements.

Many creation myths begin with the theme of birth. This may be because birth represent new life and the beginning of life on earth may have been imagined as being similar to the beginning of a child's life. This is closely related to the idea of a mother and father existing in the creation of the world. The mother and father are not always the figures which create life on earth. Sometimes the creation doesn't occur until generations after the first god came into being. A supreme being appears in almost every myth. He or she is what triggers the train of events that create the world. Sometimes there are two beings, a passive and active creator. Not all cultures imagine life starting on earth . Some believe that it originated either above or below where we live now. Still other myths claim the earth was once covered with water and the earth was brought to the surface. These are called diver-myths. According to some cultures humans and animals once lived together peacefully. However because of a sin caused by the humans they are split up. This sin is often brought on by darkness and is represented as fire. Other times the innocence of humans is taken away by a god. We continue to wonder. Even now, as the 21st century approaches we continue to make theories on how earth was created. They are our new creation myths. We base our ideas on scientific evidence. However the creation myths were based on what people saw - their observations. To reach any page on this document click on the link you want from the list below

http://www.cs.williams.edu/~lindsey/myths/myths.html

Creation Myths from around the world: http://www.gly.uga.edu/railsback/CS/CSIndex.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Creation_myth

Greek Pederasty: http://www.livius.org/ho-hz/homosexuality/homosexuality.html

IntroductionViolent debate, enthusiastic writings, shamefaced silence, flights of fantasy: few aspects of ancient society are so hotly contested as Greek pederasty, or -as we shall see below- homosexuality. Since the British classicist K.J. Dover published his influential book Greek Homosexuality in 1978, an avalanche of new studies has appeared. We can discern two approaches:

- The historical approach: scholars are looking for the (hypothetical) roots of pederasty in very ancient initiation rites and try to reconstruct a development. Usually, a lot of fantasy is required, because our sources do not often refer to these ancient rites.

- The synchronistic approach: scholars concentrate upon homosexuality in fifth and fourth-century Athens, where it was integral part of social life.

Let's start with the word "homosexual". It looks like an ancient Greek expression, but word and concept are modern inventions: the expression was coined in 1869 by the Hungarian physician Karoly Maria Benkert (1824-1882). It took several decades for the word to become current. In ancient Greece, there never was a word to describe homosexual practices: they were simply part of aphrodisia, love, which included men and women alike.

The French social critic and philosopher Michel Foucault (1926-1984) has asked whether our modern concept, which presupposes a psychological quality or a proclivity/identity, can be used to describe the situation in ancient Athens. Foucault's often-quoted answer is in the negative, because he assumes that the early nineteenth century was a discontinuity with the preceding history. And it is true: the Jewish and Christian attitudes and obsessions have never played a role in the sexual lives of the ancient Greeks. In their eyes, it was not despicable when a married man had affairs with boys, although the Athenians expected a man to have children -especially sons- with his lawful wife. The Athenian man was, according to Foucault, a macho, a penetrator, the one who forced others to do what he wanted them to do.

This view now seems outdated. Not all Athenian women have been passive and not all men were dominant. Prostitution, which was an important aspect of Athenian life, had little to do with male dominance; nor was -and this is important- Greek homosexuality restricted to pederastry between a dominant adult and a shy boy.

Introduction

Pedagogical pederasty

Recent ideas

Plato The erastes and his eromenos

(Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Leiden) Pedagogical pederastyThose scholars who prefer the historical approach are convinced that pederasty originates in Dorian initiation rites. The Dorians were the last tribe to migrate to Greece, and they are usually described as real he-men with a very masculine culture. According to the proponents of this theory, pederasty came to being on the Dorian island Crete, where grown-up men used to kidnap adolescents. It is assumed that this practice spread from Crete to the Greek mainland. In the soldiers' city Sparta, it was not uncommon when a warrior took care of a recruit and stood next to him on the battlefield, where the two men bravely protected each other. Especially in aristocratic circles, pederasty is believed to have been common. There are, indeed, a great many pictures on vases that show how an older lover, the erastes, courts a boy, the eromenos. They appear not to be of the same age: the erastes has a beard and plays an active role, whereas the adolescent has no beard and remains passive. He will never take an initiative, looks shy, and is believed not to have enjoyed the sexual union. His older lover reached an orgasm by anal or intercrural contact. ("Intercrural" means that the erastes moved his penis between the boy's thighs.) on a vase, you will never see a boy with an erection, even when his erastes touches his genitals. It is assumed by many modern scholars that as soon as the adolescent had a beard, the love affair had to be finished. He had to find an eromenos of his own.

A boy with a cock (Louvre)

It was certainly shameful when a man with a beard remained the passive partner (pathikos) and it was even worse when a man allowed himself to be penetrated by another grown-up man. The Greeks even had a pejorative expression for these people, whom were called kinaidoi. They were the targets of ridicule by the other citizens, especially comedy writers. For example, Aristophanes (c.445-c.380) shows them dressed like women, with a bra, a wig and a gown, and calls them euryprôktoi, "wide arses". In this scholarly reconstruction of ancient sexual behavior, the older lover is presented as some sort of substitute father: he is there to help his beloved one on his way to manhood and maturity, and to initiate him in the customs of grown-up people. He showed his affection with little presents, like animals (a hare or cock), but also pieces of meat, a disk, a bottle of oil, a garland, a toy, or money. This type of love affair was, according to this modern theory, based upon (sexual) reciprocity.

Recent ideasMeanwhile, however, this image of "pedagogical pederasty" has been challenged by a series of important publications like Charles Hupperts' thesis Eros Dikaios (2000). It is now clear that homosexuality was not restricted to pederasty, and that we have to study our evidence more carefully. For example, not every older erastes had a beard, and it turns out to be a modern fairy tale that the younger eromenos was never aroused. From literary sources, we know that boys had their own sexual feelings. The sixth-century Athenian poet Theognis, for example, complains about his lover's fickleness and promiscuity. Several vases show young men with an erect penis. Even when he pretends to shy away, he does not protest and does not obstruct his lover's attempt to court him.

Another objection to the traditional reconstruction of Athenian homosexuality is that there is simply no evidence that the presents shown on vases had any pedagogic or didactic value. They are just meant to seduce.

Two young, beardless lovers

(©!!!)

It also appears that the difference in age did not really matter. Not youth, but beauty was important. (The ancient ideal of male beauty: broad shoulders, large chest, muscles, a wasp's waist, protruding buttocks, big thighs, long calfs. A man's forehead was not supposed to be too high, the nose had to be straight, and he had to have a projecting lower lip, a round chin, hawk eyes, and hair like a lion. His genitals had to be small; men with big penises looked like monkeys.) There are many pictures of boys courting boys, boys playing sexual games, and adult men having intercourse. Yet, the latter was probably unusual or not spoken about, because the passive partner (pathikos) was -as we have already seen- subject to ridicule.

It is not true that homosexual love for boys was an aristocratic phenomenon. The reportory of vase paintings does not change when, in 507 BCE, democracy was introduced in Athens. On the contrary, there appears to be an increase of pederastic and other homosexual representations.

Vase showing male lovers,having sex in public. (Musei Vaticani; ©!!!)

We find many pictures of schools for martial arts, which often had a statue of the god Eros and where people exercised undressed. They were considered to be a fine place to meet one's lover. There was a law that prohibited grown-up men to stay near the dressing rooms, but if the behavior of the philosopher Socrates (469-399) is typical, this law was ignored. In fact, it seems that much of Athenian love life took place in public places: many vases show how people are looking when two people are having intercourse. There is not a single written statement that people objected to public sex. (Although it is possible that the vases are just as unrealistic as modern pornography - but see below.)

The schools for martial arts were not the only places to pick up a lover. There were brothels and casinos or kybeia. The port of Piraeus and the cemeteries outside the city seem to have been popular "cruising areas" as well, and the border between ordinary love and prostitution was arbitrary. (The difference is, of course, payment, but coins were a recent invention and in the early fifth century, attitudes towards money still had to develop.) Citizen boys often received money -as payment or as present?- which might cause some problems if they embarked upon a political career. But not everyone had this ambition or the possibility to play a decisive role in the People's Assembly. Yet, a decent citizen was supposed not to sell his body, and in c.450 BCE, when the Athenian economy had become fully monetarized, a law was proposed that people who had once prostituted themselves could not run for an office. Someone who had once sold himself was believed to be capable of selling the interests of the community as well. From now on, we find no vase paintings on which the erastes offers money to an eromenos anymore, which shows that these paintings are more or less realistic representations of what actually happened.

Later, this law was no longer applied. In the fourth century, it was not uncommon when two grown-up men shared a home. There must have been jokes about these men, but obviously, they found this an acceptable prize to pay for living with their beloved one. There was a large discrepancy between the official morals, which were expressed in the ancient laws, and everyday life.

Plato (Musei Capitolini, Roma) PlatoAs we have seen, the traditional image of pedagogical pederasty is simply mistaken, so what is its origin? The answer is the philosophy of the Athenian Plato. He has painted a very remarkable picture of his teacher Socrates, who is shown -in Plato's own words- as boy crazy. When Socrates was in the company of beautiful boys, he lost his senses. Some sort of mania (divine madness) took possession of him and he was almost unable to resist it. He often complained about the fact that he was helpless towards adolescents, and said that he could only cope with the situation by asking difficult questions to these beautiful boys and teaching them philosophy. So, according to Plato, Socrates sublimated his passion.

Xenophon (Prado, Madrid; ©!!!)

This is not just Plato's portrayal of his admired teacher. That Socrates was well-known for this attitude is more or less confirmed by another student, the mercenary leader and author Xenophon (c.430-c.354). He informs us that his master, when challenged by the presence of a good looking adolescent, remained capable of self-control, but took some measures. He did not allow the boy to embrace him, comparing his kisses to spider's bites. Sexuality and other physical contact between teacher and student were simply unacceptable. This is a bolder portrayal than that of Plato (whose Socrates sometimes yielded to the temptation), but both writers agree that their master believed that the contacts between erastes and eromenos could not only be aimed at sexual love, but also at obtaining moral wisdom and strength. A rather remarkable educational ideal.

A boy with a hare. Vase painting from the Rijksmuseum van oudheden (Leiden)

In this context, Socrates/Plato introduces an influential metaphor. Procreation, he says, can be earthly and spiritual, just like love. After all, love can be physical -aimed at the beautiful body of a boy- and spiritual, which he believes is on a higher level. This last type of love can be described as longing for something good and possessing it. The true erastes will prefer the beauty of the soul above that of the body. Instead of a material/earthly parenthood (the procreation of children) he prefers the spiritual type, which is the creation of virtue and knowledge. According to Socrates/Plato, the eromenos' understanding grows and in the end, he will be able to see a beauty that is above all earthly standards, compared to which even the most beautiful boy is nothing. In other words, by spiritually loving a beautiful beloved, the lover reaches an understanding of absolute beauty. Philosophy is, therefore, an erotical enterprise. It should be added that for Plato, the only type of real love is the love between two men, and he has dedicated two of his dialogues to that subject: the Symposium and the Phaedrus. After all, homo-erotic love is related to education and gaining knowledge, and this makes it superior to other types of love.

Socrates (Louvre, Paris)

In 399 BCE, Socrates was executed on a charge of corrupting the Athenian youth. This is a bit mysterious, because there was no Athenian law that said that people who taught bad ideas to young people ought to be killed. Socrates can not have been guilty of breaking any written law. However, his fellow-citizens have interpreted this "corruption of the youth" as a sexual corruption: they took literally Socrates' metaphor that he loved boys, and this was indeed breaking the old law of 450 (above) that forbade young citizens to sell themselves. Correctly or not, Socrates was held responsible for inducing boys to prostitution. Plato has tried to take away the blame from Socrates by pointing at his sincere and spiritual aims. In another context, he presents his master as saying that men who play the passive role are guilty of despicable and rampant behavior. After all, Socrates/Plato says, these men behave like women and are slaves of their passions. In the dialogue called Gorgias, Socrates declares that he is against all kinds of excessive sexual acts, and in Plato's main work, The State, Socrates even rejects all kinds of physical contact as some sort of unbridled behavior: the good lover treats his beloved one as a father treats his son.

It can not be said whether Plato's description of Socrates' ideas and behavior correspond to what Socrates really said and did. What we do know, however, is that it was at odds with common behavior in ancient Athens.

GREEK CULTURE

Religion The ancient Greeks were a deeply religious people. They worshipped many gods whom they believed appeared in human form and yet were endowed with superhuman strength and ageless beauty. The Iliad and the Odyssey, our earliest surviving examples of Greek literature, record men's interactions with various gods and goddesses whose characters and appearances underwent little change in the centuries that followed. While many sanctuaries honored more than a single god, usually one deity such as Zeus at Olympia or a closely linked pair of deities like Demeter and her daughter Persephone at Eleusis dominated the cult place. Elsewhere in the arts, various painted scenes on vases, and stone, terracotta and bronze sculptures portray the major gods and goddesses. The deities were depicted either by themselves or in traditional mythological situations in which they interact with humans and a broad range of minor deities, demi-gods and legendary characters.

Funerary Art The ancient Greeks did not generally leave elaborate grave goods, except for a coin in the hand to pay Charon, the ferryman to Hades, and pottery; however the epitaphios or funeral oration (from which epitaph comes) was regarded as of great importance, and animal sacrifices were made. Those who could afford them erected stone monuments, which was one of the functions of kouros statues in the Archaic period before about 500 BCE. These were not intended as portraits, but during the Hellenistic period realistic portraiture of the deceased were introduced and family groups were often depicted in bas-relief on monuments, usually surrounded by an architectural frame. The walls of tomb chambers were often painted in fresco, although few examples have survived in as good condition as the Tomb of the Diver from southern Italy. Almost the only surviving painted portraits in the classical Greek tradition are found in Egypt rather than Greece. The Fayum mummy portraits, from the very end of the classical period, were portrait faces, in a Graeco-Roman style, attached to mummies. Early Greek burials were frequently marked above ground by a large piece of pottery, and remains were also buried in urns. Pottery continued to be used extensively inside tombs and graves throughout the classical period. The larnax is a small coffin or ash-chest, usually of decorated terracotta. The two-handled loutrophoros was primarily associated with weddings, as it was used to carry water for the nuptial bath. However, it was also placed in the tombs of the unmarried, "presumably to make up in some way for what they had missed in life." The one-handled lekythos had many household uses, but outside the household its principal use was for decoration of tombs. Scenes of a descent to the underworld of Hades were often painted on these, with the dead depicted beside Hermes, Charon or both - though usually only with Charon. Small pottery figurines are often found, though it is hard to decide if these were made especially for placing in tombs; in the case of the Hellenistic Tanagra figurines this seems probably not the case. But silverware is more often found around the fringes of the Greek world, as in the royal Macedonian tombs of Vergina, or in the neighbouring cultures like those of Thrace or the Scythians.

Men Men ran the government, and spent a great deal of their time away from home. When not involved in politics, the men spent time in the fields, overseeing or working the crops, sailing, hunting, in manufacturing or in trade. For fun, in addition to drinking parties, the men enjoyed wrestling, horseback riding, and the famous Olympic Games. When the men entertained their male friends, at the popular drinking parties, their wives and daughters were not allowed to attend.

Women With the exception of ancient Sparta, Greek women had very limited freedom outside the home. They could attend weddings, funerals, some religious festivals, and could visit female neighbors for brief periods of time. In their home, Greek women were in charge. Their job was to run the house and to bear children. Most Greek women did not do housework themselves. Most Greek households had slaves. Female slaves cooked, cleaned, and worked in the fields. Male slaves watched the door, to make sure no one came in when the man of the house was away, except for female neighbors, and acted as tutors to the young male children. Wives and daughters were not allowed to watch the Olympic Games as the participants in the games did not wear clothes. Chariot racing was the only game women could win, and only then if they owned the horse. If that horse won, they received the prize.

Children The ancient Greeks considered their children to be 'youths' until they reached the age of 30! When a child was born to ancient Greek family, a naked father carried his child, in a ritual dance, around the household. Friends and relatives sent gifts. The family decorated the doorway of their home with a wreath of olives (for a boy) or a wreath of wool (for a girl). In Athens, as in most Greek city-states, with the exception of Sparta, girls stayed at home until they were married. Like their mother, they could attend certain festivals, funerals, and visit neighbors for brief periods of time. Their job was to help their mother, and to help in the fields, if necessary. Ancient Greek children played with many toys, including rattles, little clay animals, horses on 4 wheels that could be pulled on a string, yo-yo's, and terra-cotta dolls.

Education - Military Training - Sparta The goal of education in the Greek city-states was to prepare the child for adult activities as a citizen. The nature of the city-states varied greatly, and this was also true of the education they considered appropriate. In most Greek city-states, when young, the boys stayed at home, helping in the fields, sailing, and fishing. At age 6 or 7, they went to school. Both daily life and education were very different in Sparta [militant], than in Athens [arts and culture] or in the other ancient Greek city-states. The goal of education in Sparta, an authoritarian, military city-state, was to produce soldier-citizens who were well-drilled, well-disciplined marching army. Spartans believed in a life of discipline, self-denial, and simplicity. Boys were very loyal to the state of Sparta. The boys of Sparta were obliged to leave home at the age of 7 to join sternly disciplined groups under the supervision of a hierarchy of officers. From age 7 to 18, they underwent an increasingly severe course of training. Spartan boys were sent to military school at age 6 or 7. They lived, trained and slept in their the barracks of their brotherhood. At school, they were taught survival skills and other skills necessary to be a great soldier. School courses were very hard and often painful. Although students were taught to read and write, those skills were not very important to the ancient Spartans. Only warfare mattered. The boys were not fed well, and were told that it was fine to steal food as long as they did not get caught stealing. If they were caught, they were beaten. They walked barefoot, slept on hard beds, and worked at gymnastics and other physical activities such as running, jumping, javelin and discus throwing, swimming, and hunting. They were subjected to strict discipline and harsh physical punishment; indeed, they were taught to take pride in the amount of pain they could endure. At 18, Spartan boys became military cadets and learned the arts of war. At 20, they joined the state militia--a standing reserve force available for duty in time of emergency--in which they served until they were 60 years old. The typical Spartan may or may not have been able to read. But reading, writing, literature, and the arts were considered unsuitable for the soldier-citizen and were therefore not part of his education. Music and dancing were a part of that education, but only because they served military ends. Somewhere between the age of 18-20, Spartan males had to pass a difficult test of fitness, military ability, and leadership skills. Any Spartan male who did not pass these examinations became a perioikos. (The perioikos, or the middle class, were allowed to own property, have business dealings, but had no political rights and were not citizens.) If they passed, they became a full citizen and a Spartan soldier. Spartan citizens were not allowed to touch money. That was the job of the middle class. Spartan soldiers spent most of their lives with their fellow soldiers. They ate, slept, and continued to train in their brotherhood barracks. Even if they were married, they did not live with their wives and families. They lived in the barracks. Military service did not end until a Spartan male reached the age of 60. At age 60, a Spartan soldier could retire and live in their home with their family. Unlike the other Greek city-states, Sparta provided training for girls that went beyond the domestic arts. The girls were not forced to leave home, but otherwise their training was similar to that of the boys. They too learned to run, jump, throw the javelin and discus, and wrestle mightiest strangle a bull. Girls also went to school at age 6 or 7. They lived, slept and trained in their sisterhood's barracks. No one knows if their school was as cruel or as rugged as the boys school, but the girls were taught wrestling, gymnastics and combat skills. Some historians believe the two schools were very similar, and that an attempt was made to train the girls as thoroughly as they trained the boys. In any case, the Spartans believed that strong young women would produce strong babies. At age 18, if a Sparta girl passed her skills and fitness test, she would be assigned a husband and allowed to return home. If she failed, she would lose her rights as a citizen, and became a perioikos, a member of the middle class. In most of the other Greek city-states, women were required to stay inside their homes most of their lives. In Sparta, citizen women were free to move around, and enjoyed a great deal of freedom, as their husbands did not live at home.

Educations in Athens The goal of education in Athens, a democratic city-state, was to produce citizens trained in the arts of both peace and war. In ancient Athens, the purpose of education was to produce citizens trained in the arts, to prepare citizens for both peace and war. Other than requiring two years of military training that began at age 18, the state left parents to educate their sons as they saw fit. The schools were private, but the tuition was low enough so that even the poorest citizens could afford to send their children for at least a few years. Until age 6 or 7, boys generally were taught at home by their mother. Most Athenian girls had a primarily domestic education. The most highly educated women were the hetaerae, or courtesans, who attended special schools where they learned to be interesting companions for the men who could afford to maintain them. Boys attended elementary school from the time they were about age 6 or 7 until they were 13 or 14. Part of their training was gymnastics. Younger boys learned to move gracefully, do calisthenics, and play ball and other games. The older boys learned running, jumping, boxing, wrestling, and discus and javelin throwing. The boys also learned to play the lyre and sing, to count, and to read and write. But it was literature that was at the heart of their schooling. The national epic poems of the Greeks - Homer's Odyssey and Iliad - were a vital part of the life of the Athenian people. As soon as their pupils could write, the teachers dictated passages from Homer for them to take down, memorize, and later act out. Teachers and pupils also discussed the feats of the Greek heroes described by Homer. The education of mind, body, and aesthetic sense was, according to Plato, so that the boys. From age 6 to 14, they went to a neighborhood primary school or to a private school. Books were very expensive and rare, so subjects were read out-loud, and the boys had to memorize everything. To help them learn, they used writing tablets and rulers. At 13 or 14, the formal education of the poorer boys probably ended and was followed by apprenticeship at a trade. The wealthier boys continued their education under the tutelage of philosopher-teachers. Until about 390 BC there were no permanent schools and no formal courses for such higher education. Socrates, for example, wandered around Athens, stopping here or there to hold discussions with the people about all sorts of things pertaining to the conduct of man's life. But gradually, as groups of students attached themselves to one teacher or another, permanent schools were established. It was in such schools that Plato, Socrates, and Aristotle taught. The boys who attended these schools fell into more or less two groups. Those who wanted learning for its own sake studied with philosophers like Plato who taught such subjects as geometry, astronomy, harmonics (the mathematical theory of music), and arithmetic. Those who wanted training for public life studied with philosophers like Socrates who taught primarily oratory and rhetoric. In democratic Athens such training was appropriate and necessary because power rested with the men who had the ability to persuade their fellow senators to act.

Pets Birds, dogs, goats, tortoises, and mice were all popular pets. Cats, however, were not.

Homes - Courtyards Greek houses, in the 6th and 5th century B.C., were made up of two or three rooms, built around an open air courtyard, built of stone, wood, or clay bricks. Larger homes might also have a kitchen, a room for bathing, a men's dining room, and perhaps a woman's sitting area. Although the Greek women were allowed to leave their homes for only short periods of time, they could enjoy the open air, in the privacy of their courtyard. Much of ancient Greek family life centered around the courtyard. The ancient Greeks loved stories and fables. One favorite family activity was to gather in the courtyard to hear these stories, told by the mother or father. In their courtyard, Greek women might relax, chat, and sew.

Diet Most meals were enjoyed in a courtyard near the home. Greek cooking equipment was small and light and could easily be set up there. On bright, sunny days, the women probably sheltered under a covered area of their courtyard, as the ancient Greeks believed a pale complexion was a sign of beauty. Food in Ancient Greece consisted of grains, figs, wheat to make bread, barley, fruit, vegetables, breads, and cake. People in Ancient Greece also ate grapes, seafood of all kinds, and drank wine. Along the coastline, the soil was not very fertile, but the ancient Greeks used systems of irrigation and crop rotation to help solve that problem. They kept goats, for milk and cheese. They sometimes hunted for meat.

Clothing - Accesories Greek clothing was very simple. Men and women wore linen in the summer and wool in the winter. The ancient Greeks could buy cloth and clothes in the agora, the marketplace, but that was expensive. Most families made their own clothes, which were simple tunics and warm cloaks, made of linen or wool, dyed a bright color, or bleached white. Clothes were made by the mother, her daughters, and female slaves. They were often decorated to represent the city-state in which they lived. The ancient Greeks were very proud of their home city-state. Now and then, they might buy jewelry from a traveling peddler, hairpins, rings, and earrings, but only the rich could afford much jewelry. Both men and women in ancient Athens, and in most of the other city-states, used perfume, made by boiling flowers and herbs. The first real hat, the broad-brimmed petasos, was invented by the ancient Greeks. It was worn only for traveling. A chin strap held it on, so when it was not needed, as protection from the weather, it could hang down ones back. Both men and women enjoyed using mirrors and hairbrushes. Hair was curled, arranged in interesting and carefully designed styles, and held in place with scented waxes and lotions. Women kept their hair long, in braids, arranged on top of their head, or wore their hair in ponytails. Headbands, made of ribbon or metal, were very popular. Blond hair was rare. Greek admired the blonde look and many tried bleaching their hair. Men cut their hair short and, unless they were soldiers, wore beards. Barber shops first became popular in ancient Greece, and were an important part of the social life of many ancient Greek males. In the barber shop, the men exchanged political and sports news, philosophy, and gossip.

Dancing - Music Dance was very important to the ancient Greeks. They believed that dance improved both physical and emotional health. Rarely did men and women dance together. Some dances were danced by men and others by women. There were more than 200 ancient Greek dances; comic dances, warlike dances, dances for athletes and for religious worship, plus dances for weddings, funerals, and celebrations. Dance was accompanied by music played on lyres, flutes, and a wide variety of percussion instruments such as tambourines, cymbals and castanets.

Story telling The ancient Greeks loved stories. They created many marvelous stories, myths, and fables that we enjoy today, like Odysseus and the Terrible Sea and Circe, a beautiful but evil enchantress. Aesop's Fables, written by Aesop, an ancient Greek, are still read and enjoyed all over the world.

Marriage - Weddings In ancient Athens, wedding ceremonies started after dark. The veiled bride traveled from her home to the home of the groom while standing in a chariot. Her family followed the chariot on foot, carrying the gifts. Friends of the bride and groom lit the way, carrying torches and playing music to scare away evil spirits. During the wedding ceremony, the bride would eat an apple, or another piece of fruit, to show that food and other basic needs would now come from her husband. Gifts to the new couple might include baskets, furniture, jewelry, mirrors, perfume, vases filled with greenery. In ancient Sparta, the ceremony was very simple. After a tussle, to prove his superior strength, the groom would toss his bride over his shoulder and carried her off.

Slavery

Slavery played a major role in ancient Greek civilization. Slaves could be found everywhere. They worked not only as domestic servants, but as factory workers, shopkeepers, mineworkers, farm workers and as ship's crew members. There may have been as many, if not more, slaves than free people in ancient Greece. It is difficult for historians to determine exactly how many slaves there were during these times, because many did not appear any different from the poorer Greek citizens. There were many different ways in which a person could have become a slave in ancient Greece. They might have been born into slavery as the child of a slave. They might have been taken prisoner if their city was attacked in one of the many battles which took place during these times. They might have been exposed as an infant, meaning the parents abandoned their newborn baby upon a hillside or at the gates of the city to die or be claimed by a passerby. This method was not uncommon in ancient Greece. Another possible way in which one might have become a slave was if a family needed money, they might sell one of the children into slavery. Generally it was a daughter because the male children were much needed to help out with the chores or the farm. Kidnapping was another fairly common way in which one could have been sold into slavery. Slaves were treated differently in ancient Greece depending upon what their purpose was. If one was a household servant, they had a fairly good situation, at least as good as slavery could be. They were often treated almost as part of the family. They were even allowed to take part in the family rituals, like the sacrifice. Slaves were always supervised by the woman of the house who was responsible for making sure that all the slaves were kept busy and didn't get out of line. This could be quite a task as most wealthy Greek households had as many as 10-20 slaves. There were limits to what a slave could do. They could not enter the Gymnasium or the Public Assembly. They could not use their own names, but were assigned names by their master. Not all forms of slavery in ancient Greece were as tolerable as that of the domestic servant. The life of a mineworker or ship's crew member was a life of misery and danger. These people usually did not live long because of the grueling work and dangerous conditions of their work. Often those forced into these conditions were those condemned to death for committing crimes because it was understood that they wouldn't live very long under these circumstances. It is surprising to note that the police force in ancient Athens was made up mainly of slaves. Many of the clerks at the treasury office were slaves. Slavery was a very important part of ancient Greece. It played a major role in so many aspects of Greek civilization from domestic living to the infamous Athenian naval fleet. The price one might have paid for a slave in ancient Greek times varied depending on their appearance, age and attitude. Those who were healthy, attractive, young and submissive, could sell for as much as 10 minae ($180.00). Those who were old, weak and stubborn might have sold for as little as 1/2 a mina ($9.00). If there happened to be a large supply of slaves on the market, the price automatically went down. This usually happened after winning a large battle, when there were many prisoners of war. Traditionally, studies of Ancient Greece focus on the political, military and cultural achievements of Greek men. Unfortunately, the information we have about ancient Greek women is biased because it comes from various sources such as plays, philosophical tracts, vase paintings and sculptures which were completed by males. From these sources, we can conclude that Greek society was highly stratified in terms of class, race, and gender. The segregation of male and female roles within ancient Greece was justified by philosophical claims of the natural superiority of males. As we shall learn, slave women were at a disadvantage in Greek society not only because of their gender but also because of their underprivileged status in the social hierarchy. Slave labor was an essential element of the ancient world. While male slaves were assigned to agricultural and industrial work, female slaves were assigned a variety of domestic duties which included shopping, fetching water, cooking, serving food, cleaning, child-care, and wool-working. In wealthy households some of the female servants had more specialized roles to fulfil, such as housekeeper, cook or nurse. Because female slaves were literally owned by their employers, how well slaves were treated depended upon their status in the household and the temperament of their owners. As a result of her vulnerable position within household, a female slave was often subjected to sexual exploitation and physical abuse. Any children born of master-servant liaisons were disposed of because female slaves were prohibited from rearing children. Xenophon's Oceonomicus reveals that slaves were even prohibited from marrying, as marriage was deemed the social privilege of the elite citizens of Athens. In addition to their official chores in the household, slave girls also performed unofficial services. For example, there is evidence that close relationships developed between female slaves and their mistresses. Given the relative seclusion of upper-class women in the private realm of their homes, many sought out confidantes in their slave girls. For example, Euripedes' tragic character of Medea confided her deepest feelings with her nurse, who both advised and comforted her in her troubled times. Furthermore, slaves always accompanied their mistresses on excursions outside of the home. Tombstones of upstanding Athenian women often depict scenes of familiarity between the deceased and her slave companion. It is likely that a sense of their common exclusion from the masculine world of public affairs would have drawn women together, regardless of class. The only public area in which women were allowed to participate was religion. Slave women were included in some religious affairs and could be initiated to the Eleusinian Mysteries which celebrated the myth of Persephone. Thus, the fate of a Greek slave girl was determined by circumstance and more or less rested in the hands of her owners, who had the power to shape her existence. http://www.crystalinks.com/greekculture.html